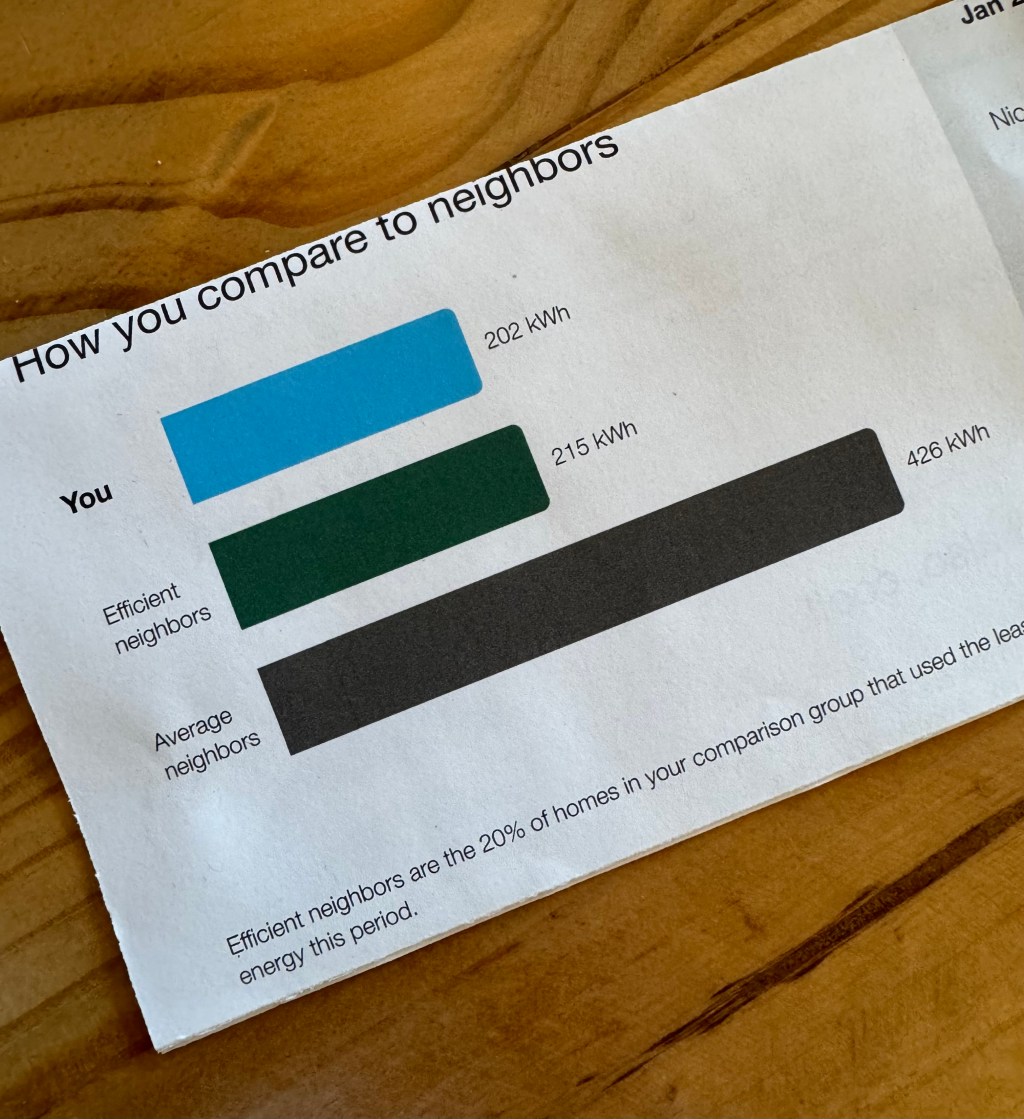

Every month the electric company sends me a home energy report along with my bill. This report gives a rating of how efficient your electricity usage was and how you’re doing compared to your neighbors. Every month I look at it with irritation, and wonder, “Who are these efficient neighbors anyway, and what are they doing differently than me? Why does my energy use always fall somewhere between them and my “average neighbors?” Recently, I got a report that my usage was “great” and I finally beat those energy-saving neighbors! For a fleeting moment I basked in the feeling of superiority.

Ask me if I’ve changed the way I use my appliances or lights since receiving this stellar report. Nope. Ask me if my less than stellar reports made me make any changes. Also, nope. So what have those reports done for me? They haven’t changed my behavior. They haven’t made me love my neighbors. But they did make me a little bit of a jerk, at least for a moment.

My monthly internal battle with my home energy report is not unlike what many of our students experience whenever school awards time comes around. Only it’s probably worse. What school awards am I referring to? You know the ones — Citizen of the Month, Best in Academics, Most Improved — I could go on. Just like my energy report, those weekly, monthly, and yearly awards and assemblies take time and resources and their effectiveness is questionable. Yet this is a deeply entrenched practice that serves few (if any) students.

To break with practices that don’t serve all children, my go-to is Cornelius Minor‘s Imagination Protocol, a process to reimagine ways we can do things differently. It starts by asking who’s being left out in the school community and how. Then reimagine the thing that’s marginalizing students to include more students. Finally, test out your idea.

Let’s apply Cornelius’ Imagination Protocol to these school-wide awards.

Who’s most left out in my school community?

• Students who don’t fit the award criteria

This seems obvious and also the point of awards, but here’s the problem — it’s impossible to separate our implicit biases from the requirements and how we choose who meets the criteria. If we use grades as the criteria, there’s an abundance of research showing that grading is rife with bias:

- Racial bias

- Gender bias

- Socioeconomic bias

When I asked a former colleague about her feelings on school awards, she lamented, “It always seemed like the same kids year after year got the awards. And they were almost always the kids who came from more stable homes and whose parents were the most involved.”

The students who had a higher socioeconomic status were the kids who consistently received achievement awards.

When we consider behavior-based awards, it’s even more unfair. I’m reminded of the book Troublemakers by Carla Shalaby (please read this book!), in which the author features four students who are deemed “troublemakers” early in their elementary school lives. Likely, they’d never meet the criteria for “outstanding citizen,” but each of their stories revealed how their unique, brilliant ways of being weren’t validated or nurtured. They weren’t inherently badly behaved kids; the current system wasn’t set up for them to succeed.

• Black and Brown students

Let’s revisit the criteria. The criteria itself can be and most often is, culturally biased. (Hat tip to colleague @SBrumbaum for the reminder.) It may be more difficult for students of the non-dominant culture to meet the criteria for receiving awards from the get-go. We already know that how the criteria is applied can be biased. Black and Brown students are disproportionately affected by classroom and school discipline policies. The same is true of positive recognition. The author of an article, “Inequality at school” from the American Psychological Association, cites studies that have shown that our implicit biases can also affect how often Black students are referred to gifted programs, as well as how teachers’ expectations may be lower. With these racial biases in place, could the distribution of awards be fair?

• Students who win awards

Wait, what? How can these students be left out when they’re the ones winning the awards? Numerous studies have shown that when people receive extrinsic rewards, their interest in whatever the reward was given for goes down. (Read Daniel Pink’s book, Drive for an in-depth look at what really motivates people.) By giving any student awards, we may inadvertently take away the joy of learning itself.

Ultimately, all students are left out when we give out school awards.

What are they left out of?

• Validation and affirmation

In a blog post, the headmaster of a school in Tucson, Arizona, explains to the school community why the school decided to do away with end of year senior awards. In his explanation, he excerpted a letter he received from one graduating senior after an end of year awards ceremony. Here’s one sentence, “Today’s awards ceremony was a huge letdown. I understand the goal is to highlight the students that succeed in our school, but instead, it ended up making the rest of us feel inadequate and ignored.” Inadequate and ignored. I’m sure that none of us became educators, so we could leave students feeling “inadequate and ignored.” This doesn’t mean that we should hand out participation trophies and awards to everyone, but it does compel us to think of different ways to validate all students’ strengths and achievements.

• Community

When we give awards for learning or behavior, it fosters competition over collaboration. Studies have even shown that students who receive rewards for kindness become less compassionate. Rather than focusing on how our actions affect others, the focus turns to how our actions become rewards for ourselves. As a classroom teacher, I decided to eliminate the use of our school’s “Eagle Bucks” given to students when they were “caught being good.” These slips of paper were put into a box, and a certain number of “bucks” would be pulled at our Monday morning assembly. The winners’ names were announced, and the students were brought up on stage to receive a trinket.

Maybe you have a similar system at your school. It always bothered me that there was still a box full of students’ names that weren’t going to be called. Were their good deeds not worthy of recognition as well? Even more troubling was the result of these “Eagle Bucks” and why I stopped giving them out. More and more, I observed students do something helpful for another student or teacher and then immediately turn around and ask, “Can I get an Eagle Buck for that?” Instead of getting satisfaction from being a helpful community member, they were in it for the “bucks.”

It’s also hard to argue that we value community when we recognize that some members are somehow better than others. As the leader of another school put it, in this KQED article, the awards suggested, “we’re one community — but you’re a little bit better.”

Instead of creating competition and pitting students against each other, we can develop more compassionate and collaborative members of a true community of learners. While there is a place for competition, as in sports and video games, learning shouldn’t be one of them, especially if we believe in the value of learning for all students.

• Joy of learning

As I mentioned earlier, numerous studies demonstrate how awarding something can cause a loss of interest in doing that thing. If you look at most schools’ mission and vision statements, there’s often a line about developing life-long learners, but when the focus becomes the award, the joy in learning is lost. One parent at the school where senior awards were eliminated, commented on the headmaster’s blog this way, “I have a senior who has worked very hard toward the goal [of] winning one of the traditional awards. This has been like a carrot on a stick in keeping her focus.” Rather than making an argument for keeping the awards, this statement reinforces what’s wrong. The student’s focus was the award at the end of the year and not on learning.

School awards not only take away the motivation and interest in learning; it can also lead to poorer quality thinking. It’s not exactly the awards, but the focus on grades and, of course, grades lead to awards. In The Case Against Grades, Alfie Kohn shares research that shows students may engage in superficial learning to get a good grade rather than deep study motivated by curiosity. When performance is the focus, students also tend to do more poorly on tasks. Awards are purportedly in place to promote academic achievement, but result in less learning and lower achievement.

Rather than focusing on rewards and performance, let’s truly develop the joy and love of learning that we want for all of our students.

How might I reimagine school awards to give more people access?

To show students that we value each of them, that we value being a community, and that we value deep learning, we can forgo school awards and instead find opportunities to celebrate every student.

• Celebrate learning throughout the year. Workshop teachers regularly take time throughout a writing or reading unit to have students share their progress with others and share their published writing at the end of a unit. You could do this in any subject area.

• Avoid underestimating the power of one-on-one interactions where you can name a student’s specific strengths.

• Instead of an end-of-year award where only a select few get honored, host an event where all students can choose something to be celebrated. For example, at one school, each child creates a poster to display something they’d like to highlight. At another, they stopped giving traditional awards at their culmination ceremony and instead featured each of their fifth grader’s baby photos along with some affirming words from a staff member.

Let’s stop depleting our joy and energy around practices that continue to cause harm and reimagine ways to make our schools places that align with our values and beliefs.

The last step in the Imagination Protocol is to test out your idea. Reach out if you’d like some support with developing and trying out an idea. I’d love to hear about your ideas and how it goes!

There are so many articles and resources out there! Here are a few favorites:

- Punished by Rewards by Alfie Kohn. The 25th-anniversary edition of this seminal work was published a few years ago.

- Why School Awards Ceremonies are a Bad Idea, and What We Should Do Instead by Lisa Van Gemert. This blog post includes several great alternatives to award ceremonies.

- Rethinking Awards Ceremonies and Honour Rolls by Joe Bower. An excellent blog post that debunks many myths around school awards.

Leave a comment